This biology professor was passionate about research into HIV and was popular with students to whom he was dedicated.

By Jeff Ristine

“ ‘The black-and-white photograph shows a gaunt HIV/AIDS activist on his deathbed in 1990, surrounded by family and cradled by his sobbing father.’ I always start with this,” Roland Wolkowicz said as he opened a brief talk on the work he was doing at his San Diego State University lab.

“You always need to remember that as an HIV researcher, there’s a human toll,” Wolkowicz continued. “I have goosebumps, I have tears every time I see this picture. So don’t forget that.”

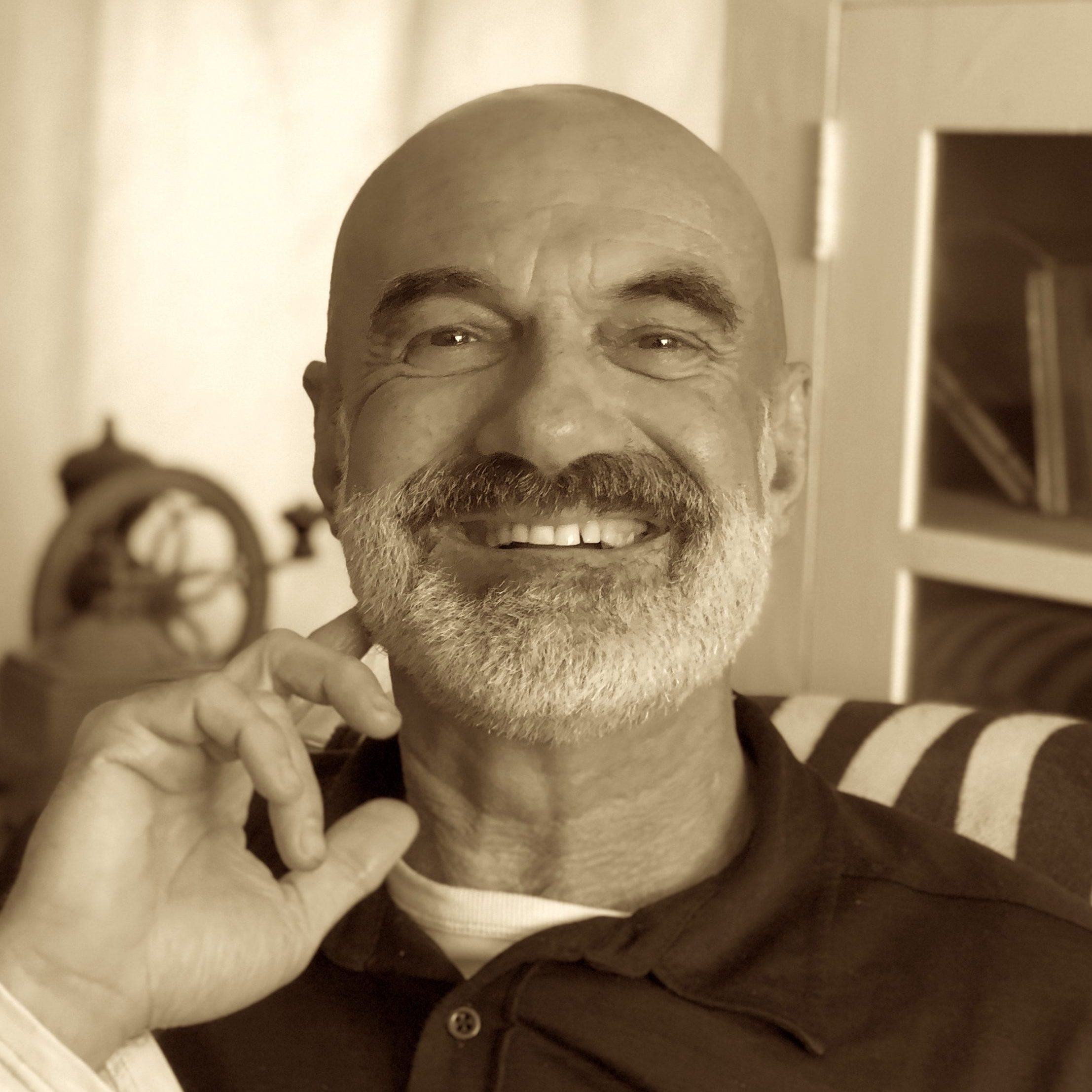

In his 14 years at SDSU, the biology professor and virologist studied HIV as well as RNA viruses that are transmitted by mosquitoes—how they affect cells and their possible drug treatments. He was known for a remarkable dedication to his students, refusing to step back from teaching even while severely weakened by advanced lung cancer and its treatment.

Wolkowicz died April 26, his 58th birthday, while hospitalized in the final stages of the disease.

Anca Segall, a fellow biology professor who led the search committee for a virologist in 2006, said Wolkowicz, who had already been engaged in HIV research at Stanford University, was recommended to the group as “a true Renaissance man.”

“When he came and interviewed in person it was clear that he was so passionate about everything he was doing, and just was an extremely energetic and knowledgeable person,” Segall said.

Wolkowicz couldn’t wait to improve the university’s then-rudimentary flow cytometry facility at SDSU, which would provide the tools needed to delve deeper into cell biology, drugs and resistance through lab tests known as assays. “He made it blossom and brought in new instruments, and established relationships with other such facilities here,” Segall said.

Benjamin Canter, a master’s student in Wolkowicz’s lab, said he was a popular professor both in undergraduate and graduate classes.

“I think his main goal was just to impact as many students as possible and to inspire as many students to go into science and research,” Canter said. “He was by far the best educator I’ve ever run into.”

To friends, colleagues and students alike he was known simply as Roland. They describe him as an exuberant personality, typically talking with animated hand gestures. He had a habit of ending sentences with “Correct?” to make sure the listener was following along, and he spoke seven languages.

“Roland believed in the power of education,” said Cameron Smurthwaite, who studied under Wolkowicz and became a close friend. “Roland believed that science could bridge gaps between classes and people, and that education was a part of this.”

Wolkowicz was born in Barcelona, Spain, and moved to Israel to study at Tel Aviv University, where he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees. In between his studies he joined the Israel Defense Forces, where he served for four years and became a captain.

In 1993 he enrolled at the Weizmann Institute of Science, a graduate-level research institution in Rehovot, just south of Tel Aviv. He completed his doctorate in 1998.

Later that year, Wolkowicz came to the United States as a postdoctoral fellow at the Stanford University School of Medicine, working as a research associate in the lab of microbiologist and immunologist Garry Nolan. He worked weekends at the genetic testing company Gene Security Network (now Natera) in San Mateo County.

Wolkowicz started at SDSU in August 2006 as an associate professor of biology and was promoted to professor in May 2016.

His interest was in viruses that have RNA in their genome. While HIV was a primary target, Wolkowicz also investigated several other viruses, transmitted by mosquitoes, that have made headlines in recent decades: West Nile, Zika, Dengue, Hepatitis C and Chikungunya.

Besides RNA, one thing they hold in common is that they primarily affect other parts of the world, and therefore don’t attract a lot of U.S. funding. “Global warming, combined with humidity and winds, has spread mosquitoes and will continue to do so,” Wolkowicz said in a profile in an industry publication in January. “It’s just a question of time; we will eventually have more of those diseases in places such as Florida.”

“He believed we should study HIV because even though we had many drugs already fighting HIV and improving lives, there were many parts of the world that didn’t have drugs available, or they had unique strains that were resistant to those (drugs),” said Smurthwaite. “He was interested in finding drugs against those viruses that affected the whole world.”

To that end, Forest Rohwer, a colleague in the biology department, said Wolkowicz had colleagues all over the world, including Brazil—a hotbed for HIV—and Europe and Japan, teaching them how to conduct assays he had developed to test drugs that might help inhibit viruses.

Wolkowicz participated in SDSU’s multi-disciplinary Viral Information Institute and was interested in the novel coronavirus now sweeping the planet, Rohwer said. “Before it really was hitting the (U.S.) very strongly we were talking about an assay that would help identify inhibitors of the coronavirus.”

Both Canter, the master’s student, and Ryan Doyle, an SDSU senior working in the lab under the Partnership Scholars program with the University of California, San Diego, were struck by Wolkowicz’s continued presence in the classroom throughout his illness.

“We would continue to have lab meetings and he would come to class even when he was feeling very weak. Even when we went away from campus he continued to use Zoom,” said Doyle, adding that Wolkowicz also continued to review papers for revisions. He encouraged students to keep up with research on the coronavirus.

A resident of North Park, Wolkowicz maintained an expansive garden. During his final days of hospitalization, when he was unable to have visitors due to coronavirus precautions, Smurthwaite said he walked Wolkowicz through the garden one last time via FaceTime, allowing him to see his artichokes, tomato plants, spinach, cabbage, apple and lemon trees and other fruits and vegetables. He kept more than 150 species of cacti.

“It was his sanctuary, his place of peace,” Smurthwaite said. “He always said, ‘This relaxes me.’”

Survivors include his mother, Anita Wolkowicz; and three younger brothers, Daniel, Victor and Walter.

In this 10-minute video, Roland described his work at an SDSU Discovery Slam.