SDSU researchers have discovered how a key protein can help the heart regulate oxygen and blood flow and repair damage.

By Padma Nagappan

In a heart attack, a series of biochemical processes leave the heart damaged, much like a car after an accident.

There is loss of tissue that needs to be rebuilt, proteins that get crushed, muscle damage, and interruptions to blood and oxygen flow to the heart. Because the heart is not very good at repairing itself, it is important to discover ways to minimize damage in the first place.

Researchers from San Diego State University’s Heart Institute discovered how one key protein in the heart can reduce damage from the attack, which could improve survival rates and heart function in those who do survive.

“The more your heart is damaged, the worse the long-term prognosis, so that’s where our research is focused,” said Chris Glembotski, molecular cardiologist and director of the SDSU Heart Institute. “We study how to make the heart more resilient to the damage of a heart attack, which would improve patient’s recovery.”

After an attack, many patients have stents put in to open up blocked arteries, which helps in the long term. But the surge of oxygen has drawbacks as well.

“The oxygen surge that occurs as soon as the stent is implanted ‘stuns’ the heart cells and some of them die, which increases irreparable damage to the heart. We found a protein that can minimize the stunning,” said Glembotski.

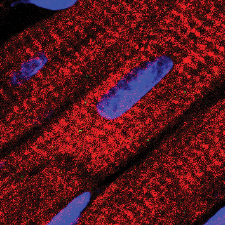

Glembotski and doctoral candidate Adrian Arrieta found that the protein, MANF (mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor), acts much like an automobile collision specialist, correcting other proteins that have misfolded.

MANF is among roughly 20,000 proteins in the heart. After Glembotski discovered its potential several years ago, Arrieta was assigned to explore it further.

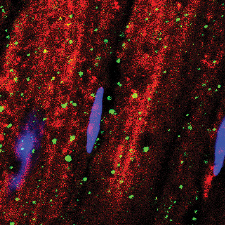

Arrieta tested genetically modified mice them by inducing a heart attack and observing how they did with and without the protein. They fared much better when MANF was present, acting as a regulator.

“This was our first clue about the importance of MANF in the heart,” Arrieta said. “It has a protective effect, but we didn’t know how it protects, because it is not structurally similar to proteins that we have previously studied.”

Arrieta found evidence that the initial oxidative stress after a heart attack—the overabundance of oxygen—is followed by a potentially damaging opposite effect. Reductive stress is like an overreaction where oxygen is used by the heart so quickly that it can become depleted. Arrieta found MANF decreased reductive stress-induced damage in mice.

Preventive Benefits if Given in the Ambulance

Eventually, the researchers anticipate this discovery could lead to the protein being administered as a drug that can be given to heart attack victims intravenously by first responders.

Immediately after a heart attack there is a ‘golden period’ when intervention to reduce the severity and damage can significantly boost chances of not only survival but also the level of functionality that the heart regains in recovery.

“One of our most interesting discoveries is our finding that MANF is a chaperone protein that keeps other proteins functional during stress,” Arrieta said. “If we could give heart attack victims more MANF, they would have less damage after a heart attack, and they would recover more quickly.”

Typically, proteins have a three-dimensional shape which enables them to do their job so the heart functions properly. If this shape is lost, heart function is impacted.

“Think of misfolded proteins like a salvage yard full of crushed automobiles,” Glembotski explained. “They were beautifully structured and highly functional at one point, but they become this misshapen mass. In a way, the same thing happens to proteins, either when they’re old, or when they experience stress, like a car in a collision.”

Next, the researchers will study MANF in the larger hearts of pigs, which respond much like humans do after a heart attack. They will also search for optimal ways to deliver MANF to the heart, again in experimental animals, as this is a critical step in the development of MANF as a drug for humans.

Their study was published May 29 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry and was selected as the editor’s choice, an honor given to only the top 2% of peer reviewed papers published in the journal. This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Rees-Stealy Research Foundation, ARCS Foundation, Inamori Foundation, and the SDSU Heart Institute.