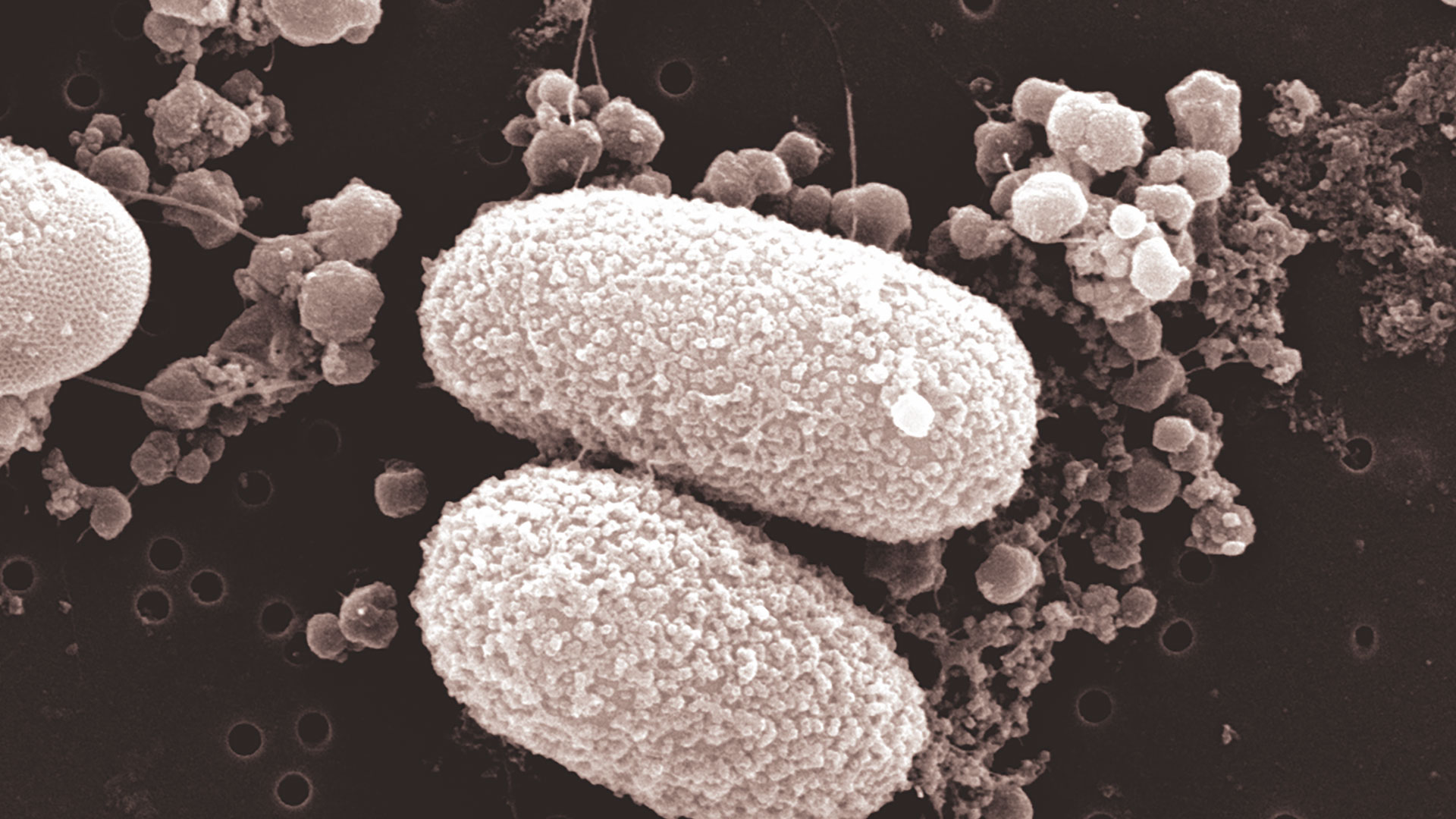

Gonto Johns returned to school after 20 years in industry, gaining career-boosting skills while exploring sustainability solutions SDSU researchers are exploring a novel way to combat climate change: methane-eating bacteria. With global temperatures climbing, seas rising and natural disasters wreaking havoc worldwide, scientists are racing to find solutions. Robert Luallen’s biology lab turns to nematodes to understand complex gut microbiome issues

Sciences-Feature

Chemistry Ph.D. student reflects on SDSU experience in final year of program

Zoom: Fueling Change

Gut health discovery made using microscopic worms — found close at hand

Why Sciences at SDSU?

SDSU’s College of Sciences prides itself on inclusive education and research innovation.

The college offers bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees across eight academic departments, with faculty who are respected experts in their disciplines as well as dedicated, thoughtful instructors. Coursework prepares students for careers in a range of fields from healthcare and biotech to academia and research.

Knowledge gained in the classroom is enhanced by hands-on learning in cutting-edge research centers on and around campus, and frequent field trips that allow students to develop the skills needed to be leaders in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

The College of Sciences operates off-campus sites such as Mount Laguna Observatory, the Coastal Marine Institute, and thousands of acres in biological science research stations, connecting SDSU advancements to the greater San Diego region.

Research Excellence

Our faculty and students regularly publish in prestigious scientific journals. Here are some of their recent publications: